Trobriand War Shields Virtual Museum

Pitt River Museum Collection

Anthropologist Steve Watters has photographed some of the world's finest

Trobriand war shield collections on his quest to understand their elaborate symbols and art

PRM 1893681 PRM 1893682 PRM 1893683 PRM 1893684 PRM 19062060 PRM 196031

Click on each shield for individual information, more photographs.

Photographed March 25, 1997 by Stephen Watters, California State University � Sacramento

Special thank you to Jeremy Coote, Curator PRM, for assistance and access.

Photograph Copyright assigned to PRM, used for educational, non-profit purposes on website only.

PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN AT PRM MAY NOT BE DOWNLOADED FROM THIS WEBSITE

The Trobriand Decorated War Shield: Symbolic or Abstract Art?

The Emblazoned Shield Controversy

By Stephen Watters

Sacramento State University, Sacramento

In the last one hundred years numerous ethnographic studies have been written about many aspects of the culture of the Trobriand Islanders. Starting with the work of missionaries groundbreaking ethnographic work and on to present-day anthropologists, the fieldwork by members of the anthropological community has continued. Interestingly, little of theearly work addressed the meaning, if any, of the designs on the decorated war shields.

Collection of the shields started during the period when early Christian missionaries and European expeditions infiltrated the Massim area in the Solomon Sea off British New Guinea. Even the in-depth field work and ethnographic writing of Bronislaw Malinowski had failed to produce a definitive answer as to what, if anything, the designs on the decorated shields meant. A 1954 article by E.R. Leach in Man started an anthropological debate regarding whether the decorated shield designs were abstract or representational and if representational, what the symbolism meant to the analysis of Trobriand culture.

What developed over the years after Leach's article are several interpretations in the anthropological literature regarding the decorated war shields. The questions raised were,

"1) are the designs on the decorated war shields symbolic of some deeper meaning,for example, containing magic spells to ward off spears thrown by the enemy;

2) or simply, are they decorative art and designs to celebrate the status of the Trobriand warrior who carried it into battle with a power of decoration? This essay will provide a brief overview of what has been written regarding the Trobriand decorated war shields, specifically as it pertains to these controversies.

Fellows' 1897-98 Emblazoned Shield Report: The Native Trobriand Explanation

In the Annual Report on British New Guinea (1897/98), the Reverend Samuel Benjamin Fellows, the first Methodist missionary to the Trobriands (Glass 1986:44), recorded the only published native interpretation of the decorated war shield design. Fellow's account was titled and was a single page appendix to the Annual Report.

The native interpretation that Fellows recorded is associated with elements of the Trobriand mythology and totemic system. Fellows also provided a diagram and explanation entitled "Interpreted Design on a Trobriand Shield," that accompanied an exhibition of four decorated war shields in the South Australian Museum, starting in approximately 1920 (I have written the Kilivilan words in italics)

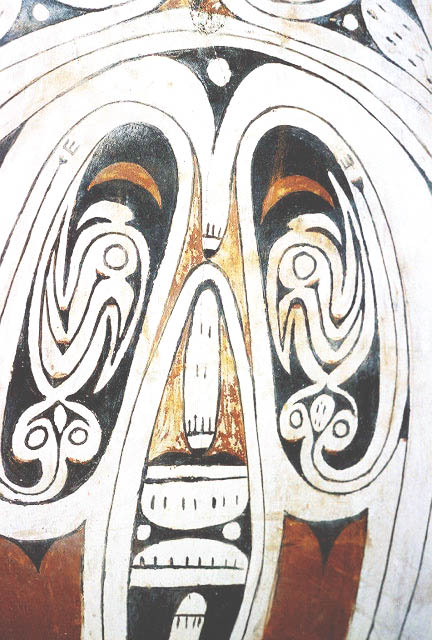

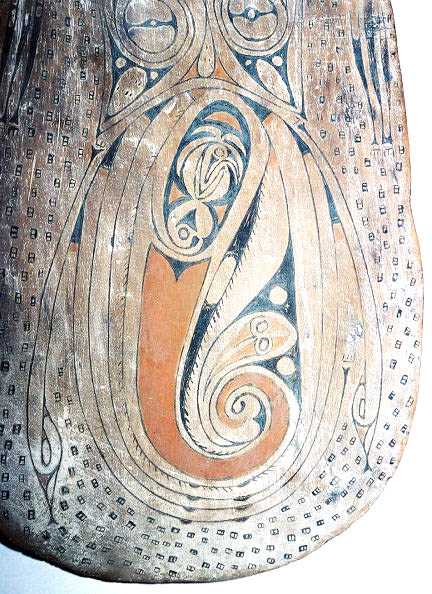

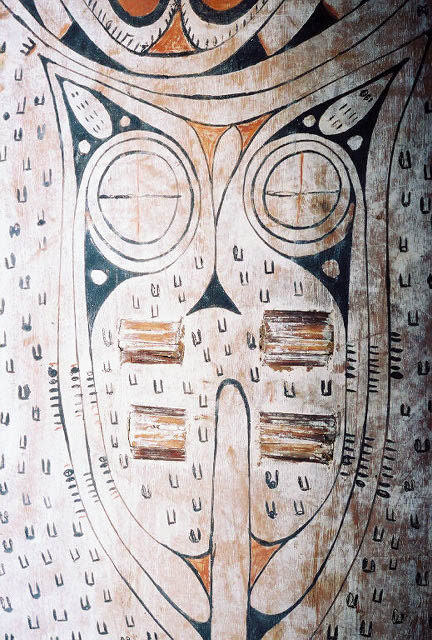

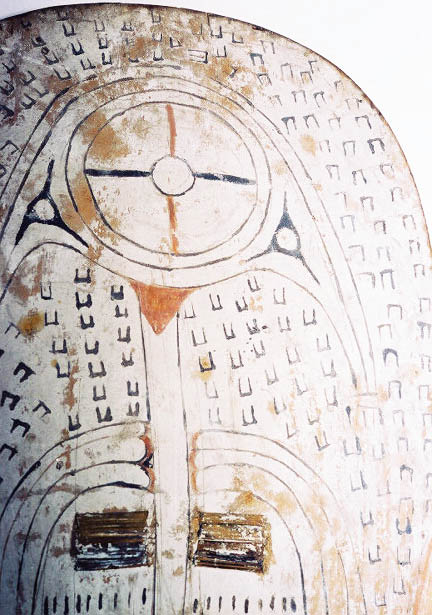

The upper portion of the shield portrays Kubwana, which is Venus or the morning star that rises when the sikwaikwa and lekoleko birds begin to crow. Three-headed snakes, Kaiuna, appear to both sides of Kubwana. Toward the middle of the shield design Sasona, small fish found in creeks and shallow sea water off beaches, as well as Siwai, a species of flat fish appear close to Ubwala or stars of lesser importance that are visible in the morning hours.

In the lower portion of the shield cluster designs representing heads of snakes, Vikia or frigate birds caught by the snakes, and the Sikwaikwa bird, which gives a sharp call before sunrise are found. A rainbow or Ludakaidoga and a Buli-buli or the tail of the manucodia (bird of paradise) is also present. There are also marks that represent spear holes centered in the lower portion of the shield (Fellows in Glass 1986:44).

The native account recorded by Fellows was validated in 1951 by a Trobriander, Lepani Gumagawa (later Watson), who was attending a conference in Adelaide and examined the collection. Gumagawa found the account accurate except for one spelling error: ludakaidoga should be lubakaidoga, a rainbow (Tindale 1959: 50). It should be noted that Baldwin reports the spelling as lupakaidoga in his account of Kilivilan vocabulary (Baldwin 1936:67).

Other Early Shield Observations

E.R. Leach shares three early observations of the Trobriand war shields all of which assumed a rather abstract design that was non-representational (Glass 1978: Ch. 2, pp. XX-XX). The first observation is from Dr. Otto Finsch, who found the shields both a high point of Melanesian art and also rare. Already in 1884, when Finsch visited the Trobriands, the shields were being produced to sell to white men (Glass: 1978: Ch.2, p. X). Finsch published the first illustration of a Trobriand war shield in Ethnologisches Atlas (1888). Other early illustrations appeared in Edge-Parkington and Heape's Album (1890) and Ratzel's Volkerkunde (1885-1890) (Glass 1978: Ch.2, p. X). I thank Glass (1978) for the following two quotes by early observers of the shields.

These rare Trobriand shields are remarkable for the artistic painting (red and black on a white background) and for the altogether singular design. These shields perhaps represent the most perfect work of painting made anywhere by Papuans (Finsch 1888:13).

The shape of the Trobriand shield is very characteristic, sometimes the surface is quite plain. When ornamented the design is simply painted on the smooth and whitened surface of the shield, with black and red pigments (Haddon 1894:240).

Malinowski's Published Comments on Trobriand Decorated War Shields

Bronislaw Malinowski was aware of the Trobriand decorated war shields during his years in the Trobriands and commented on the significance of the design in a letter to A.C. Haddon in 1918.

...the native theory of their art consists simply in a series of names given to the various individual motives, but there is no sense, no meaning to the whole design. S.B. Fellows got the names and descriptions on the shields all right, barring one or two mistakes, made through his insufficient knowledge of the language. And there is no getting beyond the disconnected agglomerate of unrelated motives. No deeper magico-religious meaning, absolutely none - and this applies to their art throughout (Malinowski in Glass 1986: 49).

Malinowski made no additional references to the Trobriand decorated war shields in his published body of work. However, in Argonauts of the Western Pacific, Malinowski included a photograph of a reenactment by Kanukubusi, the last war wizard of Kiriwina, of how he used magic to charm the shields and make them spear proof, when there were wars in the Trobriands (Malinowski 1922: Plate LVIII, 406)

Leach's Mulukuausi Ideas and the Trobriand Medusa Theory

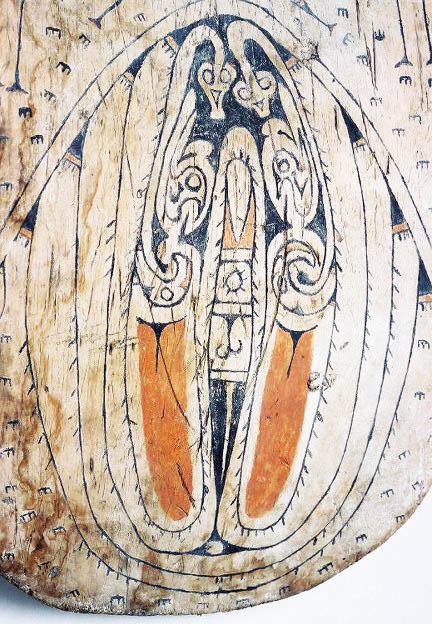

In July 1954 the debate on the meaning of the design on the decorated war shields was fueled by the publication of the article, "A Trobriand Medusa," in the journal Man, by E.R. Leach, in which he asserted that the design was that of a Trobriand flying witch or mulukuausi. According to Leach's' theory the design needs to be unfolded to see the mulukuasi (Leach 1954: 104, figure 2). Leach's theory presents two related hypotheses regarding the shield design. First, he proposes that the design, that has up to this time had been called abstract, is actually a rationally ordered representation of a winged anthropomorphic figure (Leach 1954:103).

In his analysis of this hypothesis Leach diagrams the location in the design of the face, ears, wings, feet, anus, pubic hair, clitoris, buttocks - womb, vagina, "witch testicles" and knee joints (Leach 1986:104).

At first sight some of these interpretations are likely to strike the reader as surprising and arbitrary but the analysis will be found more convincing if reference is made to the more obvious anthropomorphic figure shown in figure 2 right (Above link). It will then be seen that figure 2 left, can be derived directly from figure 2, right, by, as it were, 'folding the paper.' The indications are self-explanatory, but perhaps it should be added that the creature is supposed to have the wings and legs of a flying fox, a creature resembling a bat (Leach 1954:103).

The second hypothesis that Leach theorized in this 1954 article is that the anthropomorphic figure is actually that of a Trobriand flying witch or mulukuausi and that the mythological significance of the mulukuausi is consistent with their appearance on the decorated war shields. Leach cites Malinowski as providing the suggestion of a magical function of the design in the following quote.

When all the men were assembled at the chief's bidding in the main village the magician coram publico chanted over the shields so as to impart them the power of warding off all spears (Malinowski 1920:6).

This hypothesis of a flying witch and magical spells is then expanded by reference of the poisonous emanations that the mulukuausi emit from their vulva and anus according to Trobriand mythology. Therefore, the purpose of the design is intended as a source of powerful emanations that, when unleashed by magical spell, protect the warrior from enemy spears. Leach compares this to the story of Perseus, who carried a shield that portrayed the petrifying and beautiful head of the witch-dragon Medusa (Leach 1954: 104). Malinowski referring to Seligmann (1910) reports the following on the mulukuausi:

The orthodox view is that a woman who is a yoyova can send forth a double, which is invisible at will, but may appear in the form of a flying fox, or of a night bird or a firefly. There is also a belief that a yoyova develops in her something like an egg, or a young unripe coconut. This something is called as a matter of fact kapuwana, which is the word for small coconut. This idea remains in the native's mind in a vague, indefinite form...The kapuwana is anyhow believed to be something which in the nightly flights leaves the body of the yoyova and assumes the various forms in which the mulukuausi appears� (Malinowski 1922, p.238).

The Dobuans and Barttle Bay populations also were reported to have similar beliefs regarding witches that had large egg-like "witch testicles," from which emanations left the body to fly in the night (Fortune 1932 and Seligmann 1910). The Trobrianders believed that the flying witches appeared like fire in the sky. Leach notes that if we accept this, the designs of exaggerated anal and vaginal orifices are explained by the mythology of the flying witches and the "witch testicles" are clearly visible (see above link to Leach's Figure 2).

The Anthropological Community's Response to Leach

Response to Leach's 1954 article did not come quickly. However, almost four years later in the April 1958 issue of Man, Ronald M. Berndt from the Anthropology Center at the University of Western Australia commented on Leach's theory. Berndt felt that Leach's hypotheses failed to stand up to scrutiny due to improper methodology in his analysis of symbolic design. His failure, according to Berndt, was due to his not taking into proper account the cultural context of the Trobriand shields. Brendt pointed to the gender differences in Trobriand magic between male and female sorcery, which he felt would eliminate males taking female magic, mulukuausi, into war. Instead Brendt suggests that the design is an image of male and female genitals about to engage in coitus. He notes that Malinowski has informed us that sex and war do not mix in the Trobriands, men taking part in war must abstain from sexual intercourse (Malinowski 1939: 383). He also reminds us that in the Trobriands copulation is a fitting subject for verbal abuse. Together these cultural attitudes toward sex and war make the use of the design on the decorated war shield a visual form of abuse, designed to ridicule and shame the enemy and build personal confidence in the warrior who carries the shield. According to Berndt it is a way of making fun of the enemy (Berndt 1959: 65).

Several months later the debate takes form as Leach replies to Berndt via comments in the journal Man. Leach states, I am very well aware that the Trobrianders make a distinction between female witches and male sorcerers and that the former are figments of a paranoid imagination, any traditional war magic must have been carried out by sorcerers and rather than by witches. I am also aware that among the Trobrianders, as among the English, 'copulation is a fitting subject for verbal abuse."

All this, however, is entirely irrelevant to the question of whether the Trobriand shield design is, in intention, 'abstract' or 'representational.' My method was to give a visual demonstration that the design might be considered representational and having done so I examined the literature to find out what it might represent. Dr. Brendt proceeds the other way around: he takes it for granted that the design is representational, he looks in the literature for something that (in his view) a war shield might appropriately represent and finally he looks at the design and asserts, quite unconvincingly to my mind, the expected representation is 'unmistakable' (Leach 1958: 79).

Leach defends the characteristics of the deadly emanations of the mulukuausi as 'Medusa-like' (Leach 1958: 79). The disagreement has focused on both the methodology for determining whether the design is abstract or representational and, if representational, what is represented. Vernon Reynolds from the University College in London responds next in the July 1958 Man issue. He responds to Berndt's hypothesis by adding possible support to Brendt's hypothesis. He quotes G. Landtman's article "Papuan Magic in the Building of Houses" in Acta Academia Abocensis, Humaniona (1920), in which male warrior figures carved on the top of posts in the long houses are decorated by having the claws of hawks and male and female genital organs suspended around their necks. Reynolds believes that taking this idea and applying it to Trobriand warriors and war shield designs we can surmise that the male and female genitals depicted on Trobriand decorated war shields are there to distract the enemy, making him vulnerable to attack (Reynolds 1958: 116). However, he admits there could be a problem in accepting this position since Malinowski reports that the Trobrianders never fought without warning (Malinowski 1920:5). Reynolds also asks why so few were decorated if Brendt's idea of shaming the enemy is correct.

Describing war magic Malinowski says that,

'the magician, corant publico chanted over the shields so as to impart to them the power of warding off all spears...we see that all the shields were given some magical power which they would exercise per se in battle.... The hypothesis would then be that the decorated shields were extremely powerful (like their owners, being able to weaken the enemy's resistance by preoccupying them with sex. The design would thus be intended to work whether the enemy saw it or not (Reynolds 1958:116).

Reynolds admits that his theory is built solely on the report by Landtman in "Papuan Magic in the Building of Houses" in Acta Academia Abocensis, Humaniona (1920).

If Landtman's report of magic design to intimidate the enemy is incorrect or if the Trobriand magic is different, then Reynolds admits his hypothesis is may be inaccurate. In 1959 Professor Raymond Tindale, who was at the time was the Curator of Anthropology at the South Australian Museum in Adelaide, published his response, in Man, to the decorated shield debate, which included the Trobriand native explanation of the design. Tindale noted that the museum had been displaying four shields for forty years accompanied by an illustrated design explanation. He referred to the Fellows record of the native explanation referenced to above (Fellows 1897/98). As also noted above, the native explanation was confirmed for Tindale by a Trobriander, Lepani Gumagawa, at a conference in Adelaide. Tindale notes that when Lepani Gumagawa visited his seminar in 1951 he not only validated the native explanation but also shared the following information on two types of shields:

He stated that two kinds of shields were used on Kiriwina. Undecorated ones by ordinary folk were called kuilumuju. These were similar in shape to the one illustrated but were plain-surfaced and painted white all over. The only marks present were caused by from four to eight strips of cane forming the insertion for the cane handle. Decorated shields, called kaikataketra, were those used important men (Gumagawa in Tindale 1959: 50).

Richard F. Salisbury from the University of California at Berkeley also wrote in Man in March 1959. Salisbury provided support for the Leach theory that involved 'bisection' as an artistic technique of the shield design. Salisbury felt the intricate design was a symbol known by only a few so as to allow it to keep its power. Those who possessed and understood the shields would then become the brave and powerful warriors, the opposite of Malinowski's statement (Salisbury 1959:51).

In 1976, Frank A. Norick, in his Doctoral Dissertation for the University of California, Berkeley titled An Analysis of the Material Culture of the Trobriand Islands, Based Upon the Collection of Bronislaw Malinowski, wrote that he agreed with others, specifically Buhler, Barrow and Mountfield (1962), that Massim carving is decorative on the whole rather than having a religious or magical connotation (Norick: 1976:37). Norick continues on to question why certain design elements are restricted to one or several types of objects.

Why, for example, are certain identifiable motifs such as the "hanging snake" and the wavy-band almost always found on lime spatulas, clubs, mortars, pestles, walking sticks, axe/adze handles, and other implements, but hardly ever appear on canoe prows, splash boards, and dance paddles? If we allow that there is no symbolic significance to designs and their occurrence and since any psychological interpretation is doomed to failure from the start, then I think we have to consider a purely functional explanation (Norick 1976: 38).

Norick believes there is a correlation to be found in Trobriand design analysis between certain types of objects and the number of times designs appear on them. He finds a statistically significant match of asymmetrical designs and particular objects (Norick 1976:38). His continued analysis of these design couplings contains an approach aimed at comparing object and design shapes and use of space rather than whether or not cultural symbolism is indicated by the designs. Norick's only significant mention of decorated shield designs is that they tend to show conformity in design (Norick 1976:131).

Patrick Glass and the Trobriand Code

In 1978, Patrick L. Glass wrote a thesis for the Msc degree at the University of Salford. His thesis, titled The Trobriand Code: An Interpretation of Trobriand War Shield Designs with Implications for the Culture and Traditional Society, took the broadest look yet taken on the subject of Trobriand war shield design. Glass's main subject of inquiry was the Trobriand Virgin Birth controversy.

In the first chapter Glass argues that we need to study the anthropologist, his work and theories, holistically to get the true 'completeness' of the subject. The second chapter is a review of the Trobriand Virgin Birth controversy as expressed in the ethnographic literature. In this chapter he refers to the various conflicting war shield interpretations. In his third chapter Glass looks at the known Trobriand war shields and the native explanation. He focuses on what possible implications our interpretations may have on our knowledge of Trobriand culture. This document contains the most extensive study of the Trobriand decorated war shields contributed to the Trobriand ethnographic literature.

Glass hypothesizes a male phallic cult, which he felt could be expected in societies which claim no direct knowledge of male paternity, specifically the fertilizing aspect of semen, or for theological or metaphysical reasons cannot express the knowledge (Glass 1978:188). Glass views Topileta as the key to all aspects of Trobriand life. Topileta is cast in the role of Originator of all Trobriand life. Nobody made Topileta; so Topileta equals or is God. He originally sent forth people, yams, magic, art and so on into the Upper World because of a famine threatening in Tuma. Topiltea's wife Tenupanupaia or Bomiamuia, is hardly mentioned in discussions of Tuma (Seligmann 1910:733; and Malinowski 1916:310). If Topileta is portrayed on the decorated war shields then the genitals of his wife may also be there.

However, there is no description of Tenupanupaia or Bomiamuia in the literature. Topileta is not faithful to his wife: he copulates with all the women who come to Tuma. But Topileta is just like an ordinary man except he is covered from head to foot in tattoo, the most important person in Tuma though far bigger than an ordinary man. The phallus on the decorated war shield fits this description.

So Topileta as well as being God is also topileta, everyman: the penis carrying out its procreative role (Glass 1978: 189). In 1986 Glass authored an article in Anthropos entitled "The Trobriand Code: An Interpretation of Trobriand War Shield Designs." In this article Glass sums up beautifully the extensive work he has done on the mythological-totemic basis of his Trobriand Code theory. Here Glass proposes a three-level code in the shield designs. The first level is defined as the native or totemic explanation, as recorded by S.B. Fellows in 1897/98; the second is the X-ray or anatomical cross-section of human coitus as referred to by Berndt (1959) and demonstrating male paternity; and the third level of the Trobriand Code is the representation of Topileta, the deity, Tuma, the Trobriand heaven and underworld of the spirits, as developed by Glass in his thesis and from Trobriand mythology (Glass 1986:

Trait Origin Analysis by Gifford: The Latest Theory

In 1996 Philip C. Gifford, the Senior Scientific Assistant Emeritus at the American Museum of Natural History, wrote an interesting and different analysis of the designs on the Trobriand decorated war shields. Gifford hypothesis that the Trobriand decorated shields came about as a response to a major cultural event in the Trobriands, such as the coming of the white man.

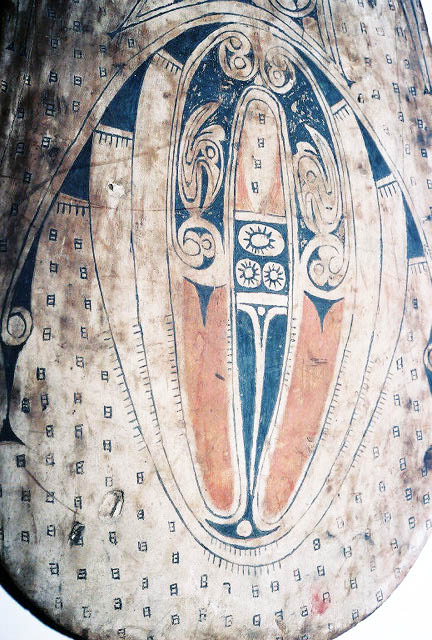

Gifford notes seven major design elements; head, belly-wheels, arms, anal anchor, legs, magical knives and fillers, which he finds present in some form on all the shields he has observed (Gifford 1996:2). Gifford notes that the elements form a human landscape on the shields. The scenario that Gifford creates is that great magic was needed at a time of enormous cultural change and the war magician looked to the ocean for inspiration.

Gifford then surmises that a shell-laced decorated war shield from the Solomon Islands drifted to shore (Gifford 1996:7, figure 4). The magician copied it, making changes and created the human landscape found on the Trobriand decorated shields. Gifford proposes that the Trobriand decorated shield design is a combination of Trobriand designs combined with that of the Solomon Islands and each Trobriand shield design may have been individualized variations of a central design. Elements were borrowed from Trobriand art and the Solomon shield and Gifford details a design relating to the production and storage of magic in the body of the magician (Gifford 1996:10).

The establishment of the new shield design provided an important contribution to Trobriand magic tradition.Everyone benefited from the decorated shield. The yam-house roof in the maze area called attention to the power and hospitality of the chief. The shield-owning warrior, when not the chief himself, had available for his protection a named, one-of-a-kind shield that recognized his warlike accomplishments. The people in general gained strength from the powerful spiritual possibilities in the decoration, accepting that the design must have been created according to the established laws of magic. The magician reserved the area of the magical knives for himself, the contact-spot for communication when reciting his protective spells. And by making his magic-making visible in the enigmatic abdomen-throat-head chart, he provided a form of immortality for all magicians (Gifford 1996:130.)

It is apparent from this brief review of the ethnographic literature that there exists variation of thought regarding what is portrayed on the shields. It appears that since the earliest recorded observations by Finsch and Haddon before 1900 and Malinowski's comments, most of the debate has been centered on what is symbolized and not whether or not the design is abstract. The native explanation, recorded by Fellows and validated fifty years later by a native Trobriander, portrays the shield design as representational of the Trobriand totemic beliefs. Leach, Brendt, Glass and finally Gifford all have presented interesting theories related to what is symbolized by the shield design. Each built on some part of earlier ethnographic work that has led to new insights about Trobriand culture.